Audio transcription:

‘Should there be

thirst, I have only to reach

for the swollen bag of skin

beside me, I have only to touch

my mouth that is meant for a flower

to it, and drink.’

— ‘Cortège’, Carl Phillips

Touch As In Grand, Unified Theory

There is a scar on my knee from where I slipped on the running track after a bout of Delhi spring rain in March 2020.

The park was within the walls of the housing society, empty of everyone but me and the stray neighbourhood cat. A Delhi Police check post on the main street outside enforced lockdown by cutting off access from one part of the city to the next. On the news, images and stories of migrant workers leaving the city: markets and malls closed, restaurants closed, domestic workers turned away.

During a time that transmuted touch into a mere theoretical, that differentially and differently affected the people around me, I felt an impulse to gather together—an attempt at a grand, unified theory of the sensory, particularly of touch. I wanted to connect and enmesh my skinned knee with the space we were asked to hold between one body and another.

Touch As In There And Gone / Touch As In And Go

A problem appeared almost immediately in this attempt: My experience of touch is anything but grand, anything but unified. While my body, once it is awake, is almost constantly seeing, hearing, smelling, and even tasting, touch remains a fleeting feeling; it’s there and then it’s gone, a sensory stimulus that leaves too brief a skin memory.

When I say that skin memory is brief, I mean that I can’t recreate the fierce singe of the Delhi summer sun on my skin once the season has set. That in my years away from snow, I couldn’t recall the pinprick of snowflakes landing onto heated cheeks. That the pressure of a body against my own disappears when that body is gone.

There is always contact being made between my skin and the world around me, of course—the chair I sit on, a draft of wind against my face as the door closes. But these stimuli often don’t register deeply enough for me; their impact feels quiet, soft. What I need to remember touch as touch (touch as being touched, touch as touching back) is stronger touch, harder touch. I need it to have intention. I need heat, I need pressure. And these ways of touching have come to me in small, rare, discrete instances that resist threading into a linear narrative, a continuity.

Touch As In: Hence, Fragments

Which is why I write here, too, in smaller, discrete units. My body’s fragmented, fragmentary experience of touch replicated in this (small) body of work.

(Don’t) Touch As In Your Face

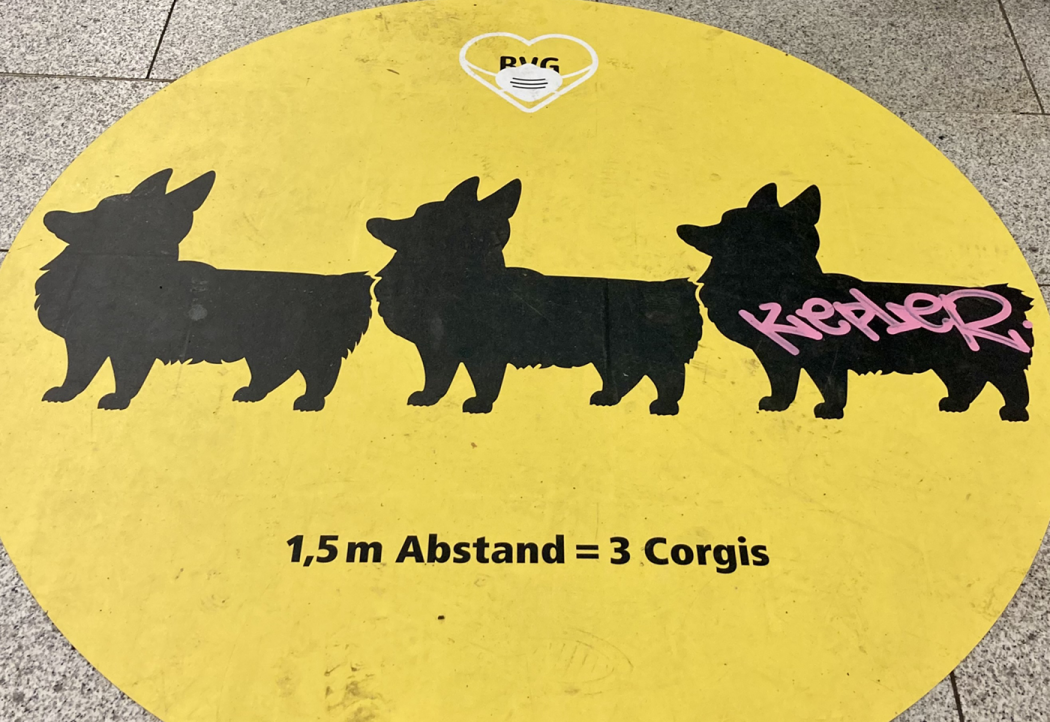

From when lockdown was announced in New Delhi in the middle of March 2020 until when I left the city in September, I can count on one hand the number of people whose bodies I touched and who touched mine. In the cityspace, the gaps between the bodies of others and my own suddenly expanded, the in-between spaces (1.5m Abstand, bitte, keep three corgis between you at all times—or in the language of Delhi markets, please stand within the circles chalked onto the ground, faded though they are by the July rains) were attended to with a caution I had rarely encountered. In the home space, we circled each other. Pushes and pulls; I sat ten feet away from my parents when visiting, masked, reading feeling through their eyes.

In the apartment I shared with my two flatmates, the heat of the kitchen stove in summer pervaded my body in a way that felt unbearable. We touched each other on shoulders and backs, shared a bed to watch films, cared for each other in the daily making of coffee. Our days were spent on Zoom in meetings with work teams, our nights on our own in our rooms.

Interlude: Seeing As In The Light

Being and becoming has, for me, been a slow process of moving from a mode of being that privileges the ‘rational,’ thinking self to one that is able to incorporate all the sensory ways in which my body registers what is around me in order to make sense (ha) of the self, of the world. The sense of sight is particularly allied with a thought-centred experience of the self—a kind of compartmentalised sensory attendance that elides what the other senses tell us.

I attribute this to the critical distance that sight allows for, sight being the sense that can take the greatest distance between the other and the self, between stimulus and response [taste, hearing, and smell can indirectly enfold distance and time, too, of course—see: ‘(A) TOUCH AS IN OF SOMETHING’]. Sight—seeing and being seen—does not leave the self or other unchanged, but distance can let you trick yourself into thinking that it does; that, even seeing, you remain an independent being with impermeable borders, unfelt and untouched.

I start at sight to trace a turning of my own body through the last ten years, a change in what I identify as its (my) needs, priorities. I spent my early twenties in college and beyond thinking mostly about sight, about cinema and film, about the relationship between what is visible and what remains unseen. When I thought about the senses and embodiment, it was precisely that: thought and theory. In those years spent focused on thinking through the world around me and my own self with a lens of vision, what did I leave out or leave behind?

Touch As In The Years Without

Skin hunger—going a long while without (strong) touch—during 2020 was not an entirely new experience for me.

Halfway through my twenties, my depression and anxiety manifested in a way that, for years, emptied the world around me of possibilities for connection and touch. I recoiled when someone reached for me. I put four or five corgis between my body and another’s, whenever I could. I put on weight and hid away my body: a pretense at a closed system. My closest friends were far away and in the new communities I was trying to find for myself, I oscillated between being open and vulnerable to shutting down and shutting out. If the independent being I had assumed myself to be in college was crumbling, I was not (yet) a person capable of sharing this self, this body, of being interdependent.

What does a body remember of touch when it is without other bodies, when it is by itself, when it is alone?

(A) Touch As In Of Something

A hypothesis: All of the five major senses are kinds of touch.

Seeing or sight is the touch of light on the internal film of the eye, hearing is the contact sound waves make with the eardrum. Smell, the brush of molecules against the olfactory receptors of the nose. And taste, of course, an intimate kind of touch with the mouth, the tongue.

Each sense bridges time and distance in its own way, too. Cinema, music, perfume, and food bring what is far away or in a different time and place closer to the sensing self. But in terms of a stimulus present for the sensing body in its immediate environment, it’s the sense of sight, for the sighted, that permits the greatest distance between one and eye (I)—glasses and contact lenses accounted for. Touch (and taste), meanwhile, require closeness, presuppose presence.

Touch As In Heat (See also: Touch As In Pressure)

Kinds of touch I longed for during the years without:

Skin against skin, mouth against mouth. The heat generated by a group of bodies in dance. Slick sweat, wet heat: fingers pressing out beads of salt water from eyebrows. A fire with laughter around it, feeling held by arms and arms. Checking whether the curry needs more spice by trying a dab on the back of a love’s hand. The warmth of the inside of the elbow and behind the knee. A friend’s arm hooking into yours—on the street, in the shop, in your room—sweaty pit stains and all. The friction of palm against leg hair stubble.

TOUCH AS IN PRESSURE (See also: TOUCH AS IN HEAT)

Kinds of touch I longed for during the lockdown months of 2020:

Hands massaging coconut oil into hair; hands rinsing the scalp to clear it out. The press of known bodies against my own in afternoon sleep. The press of known bodies against my own at a protest. The pressure of another inside me, or of arms around me at the onset of a panic attack. Strength and pressure flowing from hands to muscle, easing a knot between the shoulder blades. The crook of the neck where the mouth can linger. A heavy head asleep on a shoulder during a long car ride. The push of seated legs against your own, crammed into a small booth at the bar with coworkers and friends.

Touch As In Touché

Another hypothesis, perhaps a crucial one: to touch is to be in reciprocity, in exchange.

The contact between your skin and another’s goes both ways. Where touch is received, it is given back—with intention and consent, and then sometimes without.

Touch then lies opposed to sight as a way of being in the world. If the latter allows for the illusion of independence or distance, the former shatters those pretenses. Instead, touch—human to human, human to animal and non-human, human to the otherwise inanimate world—highlights how the body is in constant relation with what surrounds it. The body is (I am) embedded in systems of giving and receiving, embedded in encounters that may or may not change what it means to be.

Touch As In What Is It, Then, Between Us

What conditions allow a body to be a body, lean into the sensory intake of touch and know it to be true, real, meaningful?

In the photographs my brother takes of the anti-CAA protests in Delhi between 2019 and 2020, I can, in a conflation of senses, see touch. Hands on hands, passing cups of chai. Tired heads on shoulders in the nighttime. Crowds, shoulder to shoulder, walking, sitting. Bodies in opposition, too: students and cops at the JNU gate, protestors in traffic outside the Delhi Police headquarters.

Without romanticising this political moment, I want to think about what it means for an imagined community to be realised, in a moment of protest, in the flesh, in the body; to be embodied by those around you, close enough now not only to see but also to touch. In societies segregated by caste and class, ones that dehumanise their people as ‘untouchable,’ does anything change when groups of people, united in a cause, share space, share place, share air? Brush up against each other, look after each other’s thirst and hunger?

I want to say yes. And then I remember how quickly I un-remember touch.

Touch As In A Sight For Sore Eyes

To be embodied is to be constantly touched by the world: by light, sound, smell, taste, heat, pressure. What the current moment does is render us collectively more vulnerable to some kinds of touch—a condition that, differently for each of us, predates the pandemic and will continue in the aftermath.

The distance imposed between myself and others by the Covid-19 pandemic has felt qualitatively different than what came before. It is not a consequence of what I used to think of as my own lack of worth or inability to connect with those around me. It is not a consequence of estranged communities or a lack of understanding on how to be a useful, active political agent. It has felt, instead, like a period of reconciliation with what it is my body needs and hungers for—and just how much that has in common with everyone else’s bodies, what they need and hunger for.

Touch As In A Finishing

As the coronavirus pandemic takes hold, I begin to run in the small park behind the apartment block where I live. I push my legs and lungs, feel the impact of the clay track against my feet. The days slip by and the body forgets, remembers, forgets. I slip on the track and skin my knee; I run and blood runs down my shin. In a corner of the park, I find a curled up mimosa pudica or touch-me-not shrub. I wait and watch the leaves unfurl, which takes a little while. I try and pet the neighbourhood cat, who hisses at me. I pet the neighbourhood dog, who rolls over and shows me his belly. My body does not know it then, but I will end the year in a new city, in community and in reciprocity with those around me, flush with the heat and pressure of being held.

Words and Header Image by Anonymous

Anonymous is a Pisces, but prefers being known by her Gemini moon. Find her mooning over ferns at your local Hellweg.