Audio transcription:

Saint Ulrich of Zell’s day, in the year of our Lord 1518. Strasbourg. On this fine morning I walked into the market with Herr Troffea, when suddenly my feet started tapping to a rhythm I ignored. Tap tap tap. He gave me a sideways look that I pretended not to see. I bought the onions I needed to make my renowned stew, which I sometimes add meat to. Tapeti tapeta, the noise of my feet flying low, obeying a music they created themselves, as if bothered by invisible ants. I feared these signs showed that the Devil had settled in me, and I desired nothing less than to be back home, my feet hidden from the crowds that could curse my jittery limbs and might even submit me to painful exorcisms. Alas! How hard it is, to walk with dancing feet! They would simply not let me put one in front of the other. Instead, they kicked and bounced higher and harder in some detailed choreography that my hands soon joined. Herr Troffea whispered threats to my legs, as if they would rather listen to him than to me, but by then we had arrived on the city’s main square – and my coat could no longer hide my frantic movements.

The arms flew and the legs jumped high, one after the other, as I spun and spun in fear. Surely it is not pleasant to be ruled by one’s limbs, but the more I thought about it, the clearer it appeared to me: the spirit that had taken possession of my body could not be wicked. It was evidently God, who through His agent Saint Vitus, patron of dancers, commanded me to expiate our city’s great sins and misfortunes through the rapid movements of my extremities. These occurrences are not rare, after all, and God and His Saints had reason enough to be mad at us.

The gazes that landed on me were confused and frightened. I wanted to soothe them, but the wave I attempted turned my arms into elaborate curves whose gracefulness was lost on my audience. Galvanised, my legs had started to alternate kicks, arms balanced on my hips, lips gasping to swallow the summer air, already hot. I caught the glistening eye of pretty Jeanne, who for once granted me a glare. I thought about how my hair looked and when I last bathed, but shook away those useless daydreams with my swollen toes.

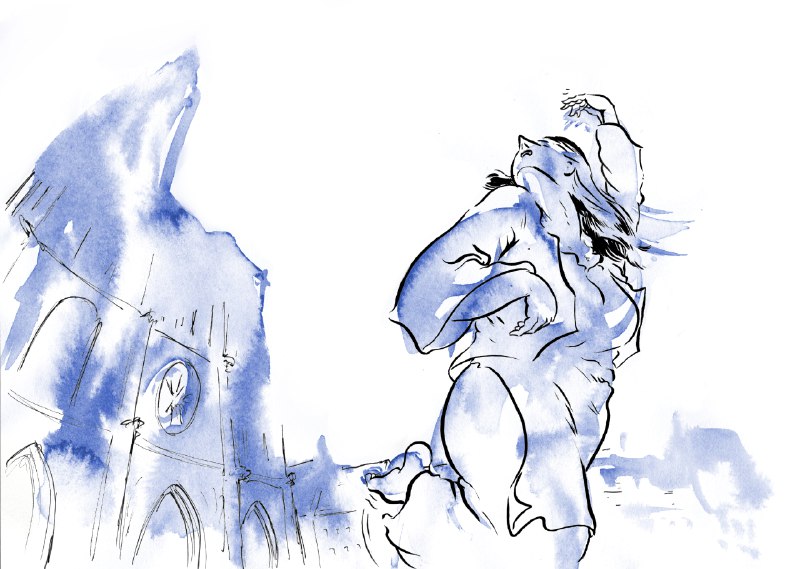

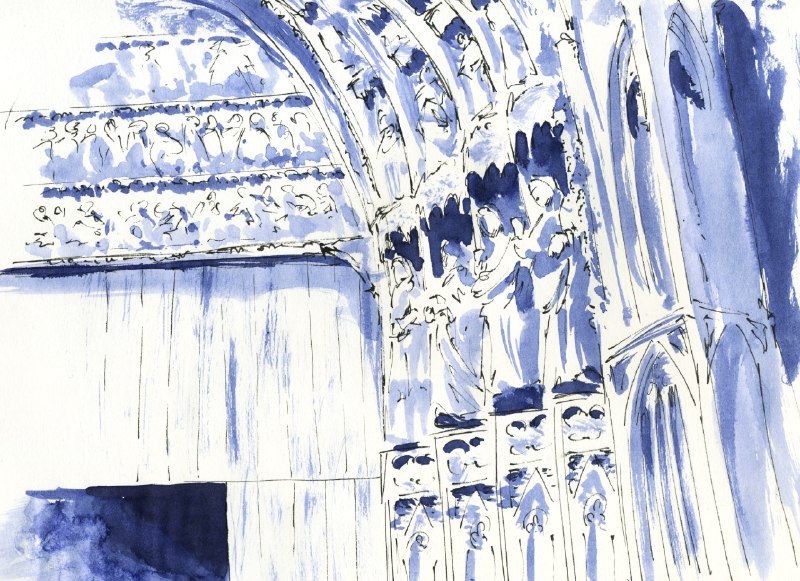

When the cathedral’s great bell began to ring the Mid-Afternoon Prayer, my thighs stiffened. I stood to attention and, like a burst of air, a shiver traveled all through my body. Faster and faster my legs lifted, and above my hair waved my arms. I must have closed my eyes, for the quiet circle that surrounded me moments before had vanished, and a few of the beholders were now inches away from me, their faces wincing, their eyes imploring the sky above us, their limbs a swarm moving at great speed, each in their own cadence. The sun was travelling upon us, making everything look like it was dancing too: the shades, the sweat on our faces, the frightened eyes set deep in their sockets, the twitches in our mouths.

The Mid-Afternoon Prayer rang anew, its vibrations echoed by the other churches of the city and through our bodies. This surprised me, because it never happens twice in the same day. The basket I carried had long ago spilled its content on the pavements of the town square, and the vegetables that rolled out of it were softly pulsating on the ground beneath our steps. Around me were more of us, and around us a circle of worried burghers, discussing. One was in the middle of an agitated conversation with my husband who wasn’t wearing his Sunday clothes anymore. Through my sweaty lips I made a special prayer to our Lord, asking for forgiveness for in my frenzy I had once more forgotten about the poor man. It’s true that he had never been a sight to remember.

Were the bells calling the Mid-Afternoon Prayer, again? Musicians were playing for us now, and we had been ushered into the market hall with ale and bread to sustain us. It was more sustenance than we had seen in the last three summers – surely some invention of our magistrates to hinder the infection. Regardless, the dance kept spreading to the mesmerized onlookers who, startled by the sudden will of their arms and legs, sometimes jumped in to join our blurry ball.

In the nights we moved slower, like grass swung by quiet waters, swaying in collective surrender. Closer to the earth, some dropped softly, one after the other, their limbs soft and their faces briefly serene, before springing again to their feet. Some remained there to be buried, while others, their clenched fists tightly clinging to the hands they had held dancing, lost all modesty in their fall.

The melody of the bells, it was covering the irritating notes of the fiddles. I thought it was the Mid-Afternoon prayer again, but then came the Morning prayer, unmistakably, and right after, the Evening prayer, reverberating with our incredulous devotion. The words of Christ blew over me, keep watch, for you do not know the day or the hour. In truth, I thought, I have completely lost track of time, and with this realisation my bloody feet jumped high in the air.

I heard later that they thought it was the work of witches. Some said I only danced to make a fool of my husband, and named my affliction chorea lasciva. Myself and others saw God’s wrath in that bizarre dancing craze – yet another sign that we were on the brink of apocalypse. Some saw frightful planetary alignments, which indeed explained many of the terrible events that happened to us then. Some blamed overheated blood, and called dancing a natural disease.

All I know is that my illness ended after six days, once they immersed me in holy water. After that, we were not allowed to hold a dance again until St. Michael’s day, lest we be fined thirty shillings. I was the first but not the last one to succumb to the dancing plague that lasted well into the season of grapes.

Words by Raphaëlle N. Victoire

Images by Jean-Côme

Raphaëlle N. Victoire lives in Berlin. She takes pleasure in writing, reading Tarot, organising for social justice movements, and dreaming about utopia.