I saw “Paris is Burning”, a documentary by Jennie Livingston, and watched the part when participants competed for the title of “FQ Realness” over and over again. To me, this category was more interesting than the others. The competitors were judged by their ability to pass as heterosexual women by acting, walking and talking like them. Once the film ended. I could not stop thinking about what the consequences were for the winner of the FQ Queen Realness trophy, and especially what the consequences were for the losers. Then I contemplated the possibility that in a society like America during the 80s, the ability to pass unnoticed on public domain without having to hide a given “femininity” made the winners lucky, because it meant they were capable of avoiding humiliating reactions against them. He wanted me to blend too, like the participants on the documentary. I knew from the beginning he would not hold my hand in public or kiss me since he was scared to say he liked me. However, I was so infatuated with J I could never have conceived of anything other than making sure he was comfortable with the situation we were in. He bought two iPhone 4 16GB phones and our relationship reached a new level: we were living far from each other, and the gift was not just the phone but the possibility to communicate any where, any time. At that point it was almost possible to dissect my life in two layers. The first one was my everyday perfected capability to blend in as J’s friend in front of his acquaintances, while the second layer would include long e-mails explaining our feelings towards each other. Maybe that is why I was so curious about the category on the documentary: I felt like one of them. The Ball Room category is confusing when you think about how it’s constructed. It is a complex framework in which various forms of representation of women are just the tip of the iceberg. This concept is immersed in a linguistic framework including forms of perception so ingrained in our communities that an action against them could result in violence. It is not only about the deconstruction of a body in order to represent an image of the heterosexual woman, it is also the assembly of that imaginary woman symbolizing the feminine champion in the most repressive sense of the word. This representation contained an idealized form originating in the participants’ own experiences, which included mass media, literature, cinema, religion and school. Assembling my own imaginary heterosexual man was not as hard as I thought. After all, I had done it before. I remember meeting his friends for the first time and looking at his frightened face as I shook their hands and introduce myself as “the friend”. At that moment my feelings of oppression were different from the ones I feel nowadays. The way we interacted with each other in the public sphere reminded me of Wayne and Garth in Wayne’s World and I have absolutely no idea how we got into that. However, the messages, IMs, Facebook chats and e-mails were my reward for having to put up with the bullshit of being the most magnificent representation of a heterosexual man—for he who had fallen in love with me. The interesting thing is that performing as a “dude” was not that different to performing the “being-a-woman” act, because both performances included the performance of the opposite in the binomial . Being-a-woman in the documentary also integrated the way men should act in front of them, together with various routines that limited and regulated their role in society. All these constructions were strictly synchronized by the binomial public-private, fixating their bodies through prosthetic devices that transform them into producing an almost “somatic fiction of femininity”1. As hard as it was, I would never have said anything to change the situation. I was scared to lose him and he was partly guilty for making me feel that way. All kinds of situations were used to prove his heterosexuality to the world: eventually women in bars and clubs became almost props for his successful performance. My life was divided into two parts, in which virtual intimacy became the number one rule governing my mind. At one point I think the performance got under my skin so much that it started to happen naturally. However, it made me more scared of what I really was. The dismantling of the body of the participant is vital for the performative action in order to achieve a desire in the subject that would celebrate the idealization of a feminine that was credible to others: and, as it was real for others it then became the truth for many. Then, after sometime, I became one with the desire he wanted to believe in. I was one: I represented his desire to become recognized by him. I was recognized, but this recognition would only come up on my phone as a synthesis of my two personalities.

[1]Preciado, Beatriz. Testo Yonki, sexo, drogas y biopolitica. Paidos, 2014. p.144

Words by Ignacio

Edited by Louise Trueheart

Illustration by Eugenia Loli

Have you read these?

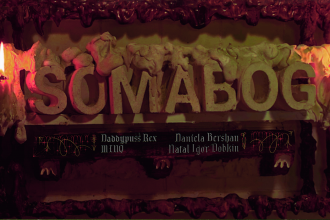

TECHNOLOGIES FOR LIBERATION (PART II)

TECHNOLOGIES FOR LIBERATION (PART III)