It wasn’t until I was in my early 20s and living with my first partner that I began to realize just how much the physical abuse I faced as a child controlled my everyday existence. It was always in the way he put the key in the door when he was coming home that caused my body to tense and my gut to recoil into a knot. And as always with my body back then I ignored it, as if to say, what my body had to tell me I could not listen. For me, it was the sound of my dad coming home from work that would trigger my flight or fight response, the car pulling into the driveway, the key turning in the door, I carry that sound with me even today.

Our body is a living archive of our memories; our muscles, our organs, our bones store trauma, and for many of us who grew up with childhood abuse, sex and intimacy can often mean an unwilling return to the scene of the crime. Part of the conditioning one experiences through abuse is the silence and denial that surrounds it. The secrecy that is enveloped within our family lives often means protecting our abusers, creating an impossible choice between asking for help and losing our primary caregivers. Which also means our ability to speak about this, even as adults, feels like an impossible choice between speaking our truth and the loss of intimacy.

The lasting effects of childhood trauma isn’t the act that happened itself; oftentimes these just get buried in a deluge of memories. Rather, it is the fact that during a primary developmental stage of our brain, while our nervous system was still forming, we grew up to expect violence. Many of us found ways to escape these environments that forged us, to escape the monster that came home at night. But for the brain that has been conditioned by thousands of years of fight or flight responses, the monsters have never left.

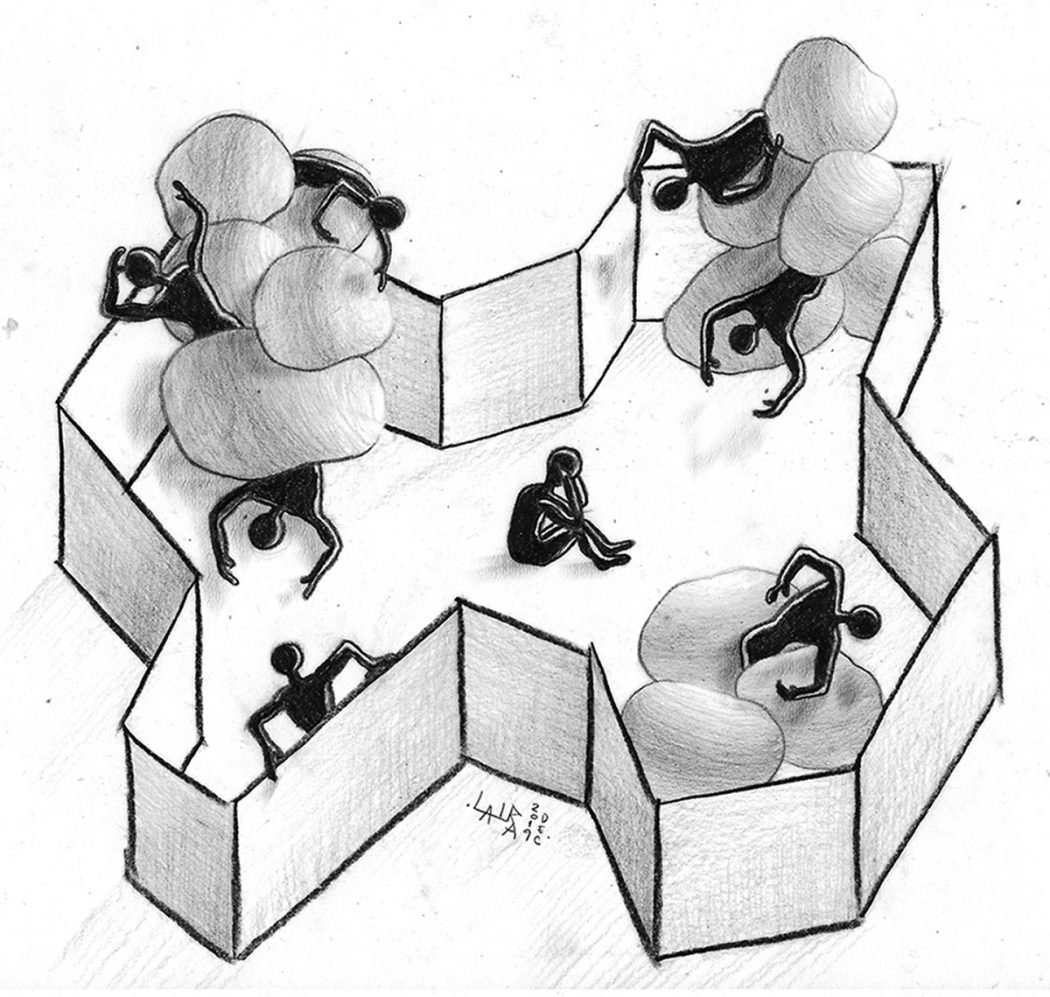

It is here we find ourselves as adults, carrying these misunderstood lessons in our mind, in our gut, and in our bodies. Despite all our desires to get close, to feel physically and emotionally safe with someone it seems everything we have learned leads us in the opposite direction.

Having sex as a survivor of childhood trauma is complicated, where the most innocuous of situations that move towards intimacy could trigger a flight of fight response. It has taken most of my sexually active life to start peeling away the layers where I push people away or hold myself back from getting close to someone, to see all the ways I disassociate from my body during sex or the way I disassociate from who I am with. And eventually, to see my healing begin when I can become more present with myself, my body, and someone else.

Sex and intimacy for queer people can feel strange largely in part because we live in a world that treats our very existence as a threat to the social order, which means joy through intimacy can be a revolutionary act. Yet, for survivors of abuse it also means learning to listen to our bodies first and giving ourselves permission to feel uncomfortable. Western queer culture has adopted an identity of hypersexulization as a modality for liberation. It can often feel as if one is not truly queer, truly free if we don’t convey this publicly or immediately sexualize ourselves in a confident way. None of this is wrong, in fact this can all be quite freeing, but to recognize how your mind, your soul, your body feels through this process can begin to unwind some of the barriers one has to feel closer, safer, more connected to another person.

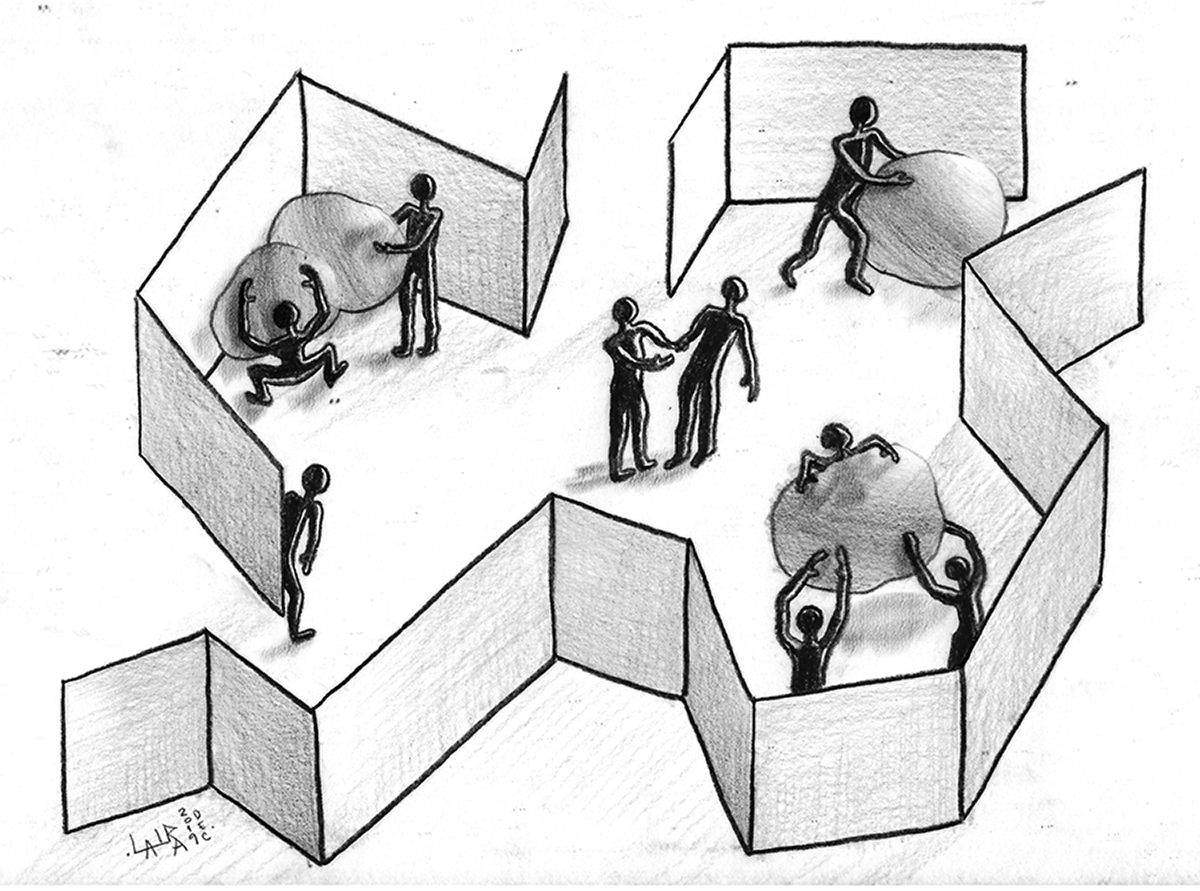

For me, it required developing a relationship with how I set boundaries. To learn when my body is telling me something doesn’t feel right, to listen to it when it needs things to slow down, and to develop the strength to communicate that to my partner, even when it feels silly to do so. Vocalizing our needs before, during, and after sex can feel hard at first; a huge part of our childhoods were about masking our needs, but it becomes an important factor in setting up the conditions for us to have the meaningful experience and connection we are searching for.

This also might mean disclosing some or part of our trauma to the person(s) we are with, which opens the terrifying prospect that the person you want to tell isn’t equipped to handle it. People carry their own traumas, which you are not in control of, and how they handle our story is not a reflection of you. What we are in control of is the expectation that we deserve love, care, and to be respected, and if their response doesn’t meet that, then it probably isn’t worth hanging around for anything else.

We all have to discover our own paths towards healing but it begins with the painful process of admitting what happened was real and significant. Sex can be fun, kinky, and joyful and hopefully it always is, but there are also times where it can also be scary, uncertain, and painful and that’s ok too. The process of becoming an adult means we are now fully in control of our lives, and we get to determine how and what happens to our bodies, like it always should have been. It also means coming to terms with the fact that we are not merely the products of our experiences, rather molders of our present, capable of healing and joy. Taking control of my sexual relationships has allowed me to take control of other aspects of my life. By developing the courage to express my needs in the most intimate of settings has also allowed me to express them in other parts of my life.

Doing the work that uncovers and addresses this trauma is to awaken pain that has been stored in our bodies and our minds. This is never easy, but it also begins the process of understanding how and when people are hurting you in the present.

None of this is easy – I was well in my 30s when I was finally able to do the work that was necessary to make meaningful strides for taking ownership of my sexual life. But the first step was the realization that I wanted more, and that I deserved that. We can feel so alone in this area, but we aren’t: this affects more people than we realize. From my experience, I have learned, the world is far more empathetic and loving than what my early years taught me. It just takes the courage to begin speaking about the impossible to start seeing what can become.

Words by Sailesh Naidu

Illustrations by Laura Sobenes

Sailesh Naidu is a gender non-conforming poet, performance artist, and comedian based in Berlin, Germany. Born in the United States with roots in India, Sailesh’s work delves into the ideas of gender, sexuality, decolonization, and the body. A former German Chancellor’s Fellow, they have worked in the fields of migration, education, and gender for over a decade, with their projects winning the acclaim of the New York Times and PBS New Hour. Sailesh is currently working on their first poetry book, Territory.