From the beginning, I knew the diary wasn’t working, but I couldn’t stop writing. I couldn’t think of any other way to avoid getting lost in time.

— Sarah Manguso, from Ongoingness, The End of a Diary

Gabriela Gordillo is an artist, born in Mexico City and living and working since 2015 in Linz, Austria. In this piece, she reflects on the work that her father has undertaken for many years, since her adolescence — taking photographs of the moon — and juxtaposes it with her thoughts about Minute/Year, a durational sound-based installation artwork by Kata Kovács and Tom O’Doherty.

Audio version of this article read by Cathy Walsh.

The act of photographing can be seen as an intimate moment. From the sudden juxtaposition of the observer, the camera, and the observed, an exceptional arrangement emerges, articulated by time and space. After this moment, an image will remain, while the photographer and the object are already moving on, in different trajectories.

When I was a teenager, my father used to take pictures of the moon every night. The memory card was always full with high-resolution pictures that looked the same. He went to the rooftop and spent some time there — with the idea of capturing a ‘unique’ moment of the sky. After a while, not only did he get better photographs, but he also developed a familiarity with the subject: between pictures that I saw as identical, he could spot contrasts. The moon, from one day to the next, was almost the same, but slightly different.

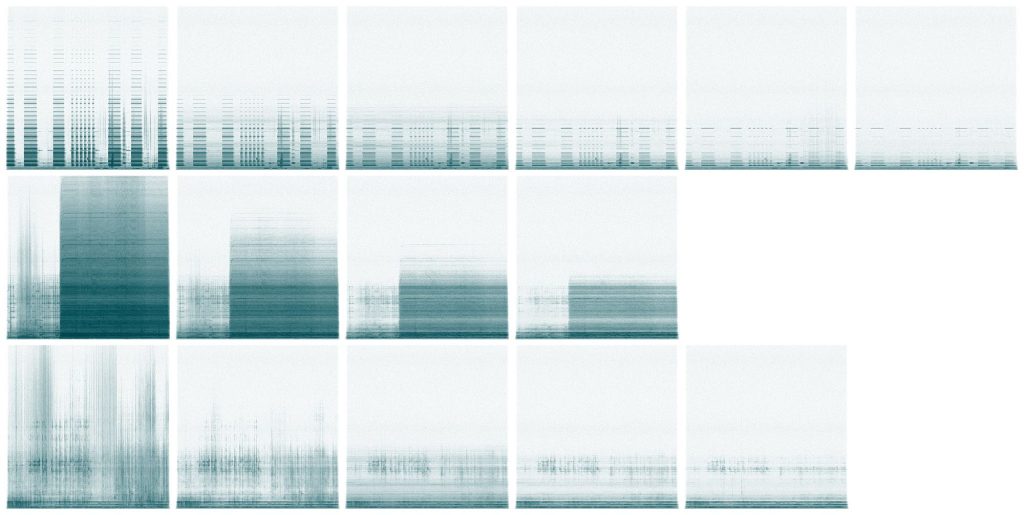

Since January 2016, the sound-based artwork Minute/Year has created one recording every day, each one minute long. The installation’s function is repetitive, although each captured minute is different. A unique spectrogram — an image of the recorded frequencies — is published in different channels online, and added to a digital archive that binds the year, day by day. It is then stored in 365 audio files, which corresponds to just over six hours of recordings each year.

Time-lapse video of the spectrogram images generated by Minute/Year during the first 90 days of recordings in 2020, demonstrating the visual outcomes of the daily process of layering and fading.

In the comparison of two pictures of the moon, or the action of looking at it twice, we deduce time. Two instances of a single thing can only happen if there is a mechanism that hides its previous states. When we see a repeated instance of the thing (identical but not equal), it reveals rhythm. When the moon appears the same after 28 days, in a full cycle, it triggers our memory, our capacity to enumerate.

In its iterations, Minute/Year not only reproduces the cyclical nature of time, but also the linear dimension: each new recording is a re-recording of the previous one, and so each recording includes a reminiscence of an immediate past, drawing a temporal direction, allowing for its contextualisation through its location in the array of the year. The mechanism is additive, as it sums up the serial instances — and, simultaneously, subtractive: with every new sound, the loudness of the playback decreases, provoking a slow fade-out of the present

Forgetting makes me think that some goodbyes are forever. Sounds and words vanish from the mind, material states and ‘the now’ are always in the process of disappearing. But detaching from this passing time helps us to breathe, feel the present, and foresee the future.

The constant of the moon is change. Every time you look at it, you know it is in transition and it won’t stay for long. It’s always on its track, certainly not waiting for you. But eventually, despite making no promises, it returns. Its second constant is recurrence, which makes the whole thing not a goodbye but rather a slow dance.

When I saw my dad taking pictures every time the moon was up, I didn’t understand the need for yet another photograph. “Today it’s not so beautiful,” I thought, sometimes. “It’s not even full moon, it’s just transitioning” — defining, for myself, the outstanding in contrast to the ordinary. Still, I could see — though not necessarily understand — the pleasure in chasing each picture, and the intention of capturing something else that was not captured before, in a similar setting.

Human memory has subjective or physiological barriers to remember things as they were, but still creates the impression of experience. Maybe memory is something that lives within us, even if we don’t recall it. An archive, on the contrary, retains a different temporality. It holds the permanence of a material thread, a permanence that doesn’t fade but that can be touched and remains to be analyzed. Through these tokens, we can pretend to bring the past into our present space-time.

Both the moon and Minute/Year are part of other rhythms outside of themselves. The moon orchestrates tides, magnetic fields, and menstrual cycles; it visits many nights around the globe every twenty-four hours. Minute/Year listens to the sounds of nature, to urban environments, to indecipherable human language and humming machines. It computes from a Raspberry Pi, synchronizes with the internet, with digital platforms and with power supplies.

A longer cycle of Minute/Year happens every trip around the sun, in sync with its change of location. On December 31st, the piece finishes running in one place and starts in a new location, through different hardware. This transposition keeps the piece re-locating into different contexts, finding variations.

Sometimes, time feels like a golden breeze in which change is refreshing, offering a new beginning. Other times it can seem like a sea of memories that invites us to submerge ourselves, and stay forever in the same place. Acknowledging the two locates me, for a moment, outside of time. It gives me a rest with no tides.

My father used to select and clean up the digital pictures at night, in folders organized by date and topic. With this archive, there was no upcoming project, but definitely a dedication to wandering through time.

Gabriela Gordillo is an artist, born in Mexico City and living and working in Linz, Austria since 2015. Gabriela creates participatory and social interfaces through an interdisciplinary approach. In her work, sound and listening represent attention to the invisible and material for the sketching of temporal structures.