Research is a dirty word—not because it has to be but because those who often wield the levers of power make it that way. As a historian, I often struggle with narrating the stories for those who passed away – especially those who left little written trace. Archives and oral histories are often central to the historian’s research practice; scholars can spend years of their lives convening with ancient texts. For example, diplomatic records can be a gold mine for uncovering espionage disguised as cordial politics. But what does one do when nothing is written? One struggle endemic to my historical work has been finding the voice of the enslaved, the desires of the queer, and the sentiments of the illiterate. In some ways, this is grounded in finding a home in my practice, a way to uncover the many domiciles that my ancestors made and remade. The near erasure of these people is not an accident. It is by design.

While I recognize that no archive is innocent, my family history is grounded on non-textual sources. We are people who travel. And what I find is that Haitian diasporic women serve as healers, historians, and more. Starting from the continent of Africa, to the slave ships that brought them to Saint-Domingue during European colonialism in the Caribbean, up to present day Haiti, Haitians have continued to redefine the ways in which they seek and use healing. Mapping enslaved narratives is not just an act of narration, but it is an embodied experience that can incorporate the joy of Haitian processional music, like that of mizik rasin band such as Boukman Eskeryans.

In recent years, the story that I was unable to tell was the story about myself—the story of my Haitian ancestors, their inner struggles and moments of jubilation. The historical absence of my lineage in the archive who were stolen from Africa is not unique to me. It stands true for many African descended people whose families still live in the settler colonial countries of the New World from Brazil to Canada. Part of the trouble of reckoning with this past is engaging with the archives that bear the strange fruit in the shape of, for example, captain logs and inventory lists from the trans-Atlantic slave trade until the last Haitian dictatorship: Archives nationales de France, Les Archives Nationales d’Haiti, the British National Archives, the Schomburg Center for Research on Black Culture and more. In Silencing the Past, the late Haitian anthropologist, Michel Rolph-Troillot juxtaposed the West’s erasure of Haitian history in light of the West’s present anxieties about Black liberation. He wrote, “History is the fruit of power, but power itself is never so transparent that its analysis becomes superfluous. The ultimate mark of power may be its invisibility; the ultimate challenge, the exposition of its roots.” Recently, Dr. Nicole Willson discovered the will of Marie-Louise Christophe, the queen of Haiti. She died in Pisa in 1851. In 2009, I saw her statue at the remains of Sans Souci, the palace that had been built in northern Haiti by her husband, Henri Christope, the emperor of northern Haiti. This tension between those who are documented and those who are left out is precisely what I want to blur.

The evidence for non-elite black history is far-reaching, from slave testimonies such as The History of Mary Prince, the first written narrative of a formerly enslaved woman from the Americas, to ethnographic accounts by Black American writer Zora Neale’s Tell My Horse, an early twentieth century text that documents voodoo rituals in Haiti and Jamaica. How do we use more sources developed by Black women to mark the obstinate and non-elite stories of the past? In her recent book, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, the African American scholar Sadiyya Hartman suggest that one can “employ a mode of close narration” to capture these untold stories. This act of close reading for invisible subjects requires a bit of learning and unlearning, yet hidden beyond that is a process of excavation and repair. That is to say, learning to capture the disorder of the world that produced these inequalities and to hone in on the narratives that are already living amongst us, in other words, through oral histories, food, music, and more.

edna bonhomme, self-created family archive, installed as part of Scan the Difference, VBKÖ, Vienna, Austria, 15-21 May 2019. Photograph by edna bonhomme.

In an attempt to honor the past through an act of repair, I bypassed the traditional archives, their hierarchies of power, and the act of (re)imagination through personal narration, mapping slavery, collective cooking with members of the collective COVEN BERLIN, and an assemblage of people who trusted our journey enough to engage in history through action.

In order to do that I faced the history that I knew. I was born and raised in apartheid America, on the land of the Seminole people. The land was first colonized by the Spanish and then the British and now it is called Florida. My family’s trans-Atlantic history is an indication of our proximity to freedom and notions of “human.” Our precarity is, as Sylvia Wynter remarks, “unsettling the coloniality.” When my ancestors survived the Middle Passage and were forced to work the plantations on Arawak land in the Caribbean Sea, they soon found out that “our bodies are not our own.”* Instead, they were commodities.

As the recent New York Times 1619 Project has documented, the Transatlantic slave trade was not a linear phenomenon. It was comprised of an intricate relationship between Western Europe, Africa, and the New World. Slaves who arrived on the shores of Saint-Domingue, beginning in the sixteenth century, were taken from various parts of West and Central Africa. Upon arrival to the New World, they bore the enormous burden of being viewed as laboring property, or “enslaved workers.” As such, they suffered the indelicate balance of needing to be healthy enough to increase their productivity, while being perceived as unworthy of medical care. On the plantations of Saint-Domingue, slaves had harsh exposure to the elements, imaginably poor living conditions, and long, miserable, back-breaking work days. They also suffered from malnutrition and protein, iron, and Vitamin B deficiencies, among others.

My family members were dissidents under the dictatorships, people who took a boat from Haiti to Miami, aware of their radical past, and proud. As a child, I was presented with bits of our history, not through books but through folklore, through music videos, through Rara. Boukman Eksperyans’ song Ke m Pa Sote, produced in 1990 after the dictatorship and during a military coup, along with other celebratory music, inspired working class Haitians to revive the rara tradition. Beyond that, the celebration by Rara groups such as Boukman Eksperyans gestures towards Voodoo, which has served as a spiritual rock for the African diaspora during and post slave-trade.

How do we find the working poor, the displaced, dispossessed, and disenchanted in the archives?

Sometimes you cannot.

With limited access to proper care, slaves had to navigate a new territory and a new identity in order to form a system to help them survive daily life. Through their tactics of survival and their politics of care, slaves were able to familiarize themselves with local herbal resources in Haiti. Many of the holistic healing practices used during colonial Haiti are still used today. Enslaved people used these materials for healing and spiritual repair and they reflected the resistance and resilience of the slaves in the face of one of the most inhumane periods in history. What I came to know is that although their names and their contributions would not be found at the Archives Nationales d’Haiti, their capacity to pass on knowledge about the Haitian revolution through stories and healing practices was, in some sense, an alternative archive.

Because I am the descendant of Black farmers and fisher people, we have no records, no objects, no birth certificates, just inherited debt from an uneven system built to relegate us to the non-human. But that narrative is not complete. Black women such as Cécile Fatiman were central to my liberation because they were the narrators and archivists for the sources that never existed.

How do we care for each other in the face of trauma? We repair ourselves with the flora that can protect us. Scientists have found that Haiti is saturated with medicinal plants, leaving people to use fresh ginger to improve the immune system, and in some cases, using castor oil to heal sore muscles. Repair can also mean learning the herbal practices that simultaneously operated as part of somatic healing and as an act of resistance in the face of oppression. I am not a master herbalist and I am not a member of the voodoo religion, but the process of inquiring and excavating the historical trauma provides some entry point to repair.

In this way, re-narrating the archives through plants re-orients what home can be. The late and great writer Toni Morrison remarked, “Home is something very peculiar. Something special, mystical, hopeful, restful.” I do not have a home, but I have been housed in many places that are deeply entrenched in the genocide of indigenous subjects and the free labor of enslaved subjects. Home is not solely about the trauma. It can be a place of reckoning, a place of healing, a place that one can claim.

*This is referencing my poem, “Our bodies were never our own”

by e. bonhomme

Our bodies are not our own

Whether we picked tobacco on the rolling hills of Saint Domingue

Or we stood on the front porch of a West Virginia estate

Whether we rose at daybreak

On a sweltering summer day

Right before the dew

Evaporated from the orchids

When we laid next to our kin

On the dewy ebony floor

While we shivered ourselves to sleep

When all we wanted to do was kiss

Our first love but the slave master kept us at bay

Our bodies are not our own

During the inferno in the South Bronx

When derelict brownstones are set ablaze

When we stand at border control

With unfit passports and melanin rich skin

And we are told that we can’t get in

When we walk into a hospital for treatment

and told our pain is in our is in our head

When the bus depot pollutes the air in Harlem

When the auto factories poison our water in Flint, Michigan

When the petrol company destroys our ancestral land

THIS IS MEDICAL APARTHEID

We know that our flesh is full

And our smiles are wide

When it glistens in the afternoon Sun

Our bodies in their capacity to endure are beautiful

Words and Images by edna bonhomme

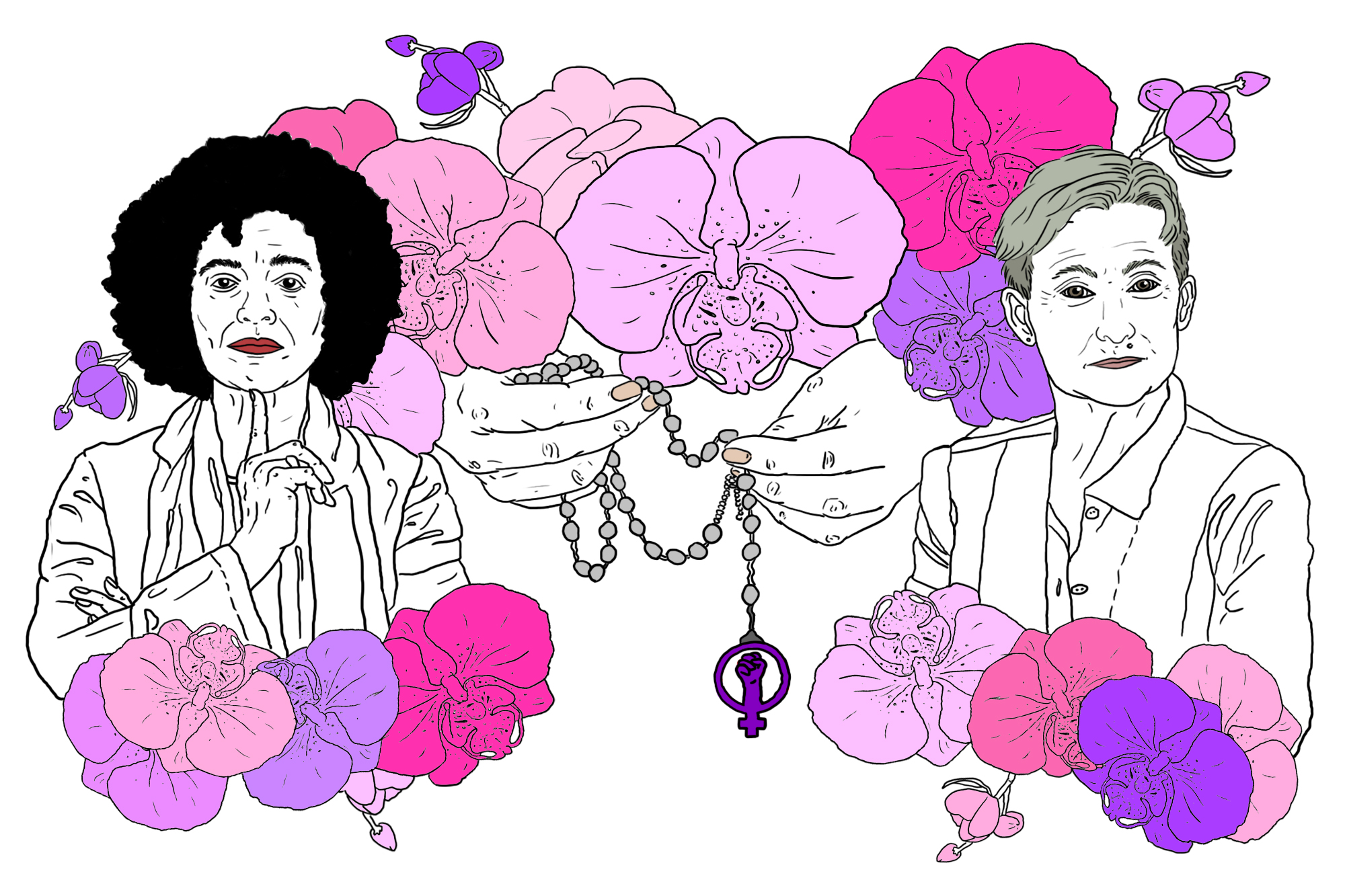

Header Image by Lara Holenweger

edna bonhomme is a curator, historian, and writer whose work interrogates the archeologies of colonial science, embodiment, and surveillance. She is currently based in Berlin, Germany. You can find out more about her work at www.ednabonhomme.com or on Twitter.