Watching shows, I often feel that the performers try to make me feel a certain way: to laugh, to cry, to be turned on, to be shocked, to feel catharsis. In Earthbound Squatters, the performers were trying to make me feel that I had to pee. When I realized what they were doing, I became a bit scared and was angry at them. I was trapped, seated, an audience member with a big bottle of beer, while they did everything in their power to remind me of peeing.

This began with drinking; the performers loudly gulped water, lots of water. Next, the so-called ‘piss DJ’ played sounds of pouring, trickling water, and the performers whispered hisses and ‘psssh’es, and other lulling, wet sounds.

The dance itself started in a minimalistic way, with short, rigid movements, that somehow became more strained, almost painful. They were lifting their legs and letting the urine build up – you could see them making an effort to contain something. And as their bladders filled, so did mine.

A wave of unease swept over me, and I could feel it slowly growing through the rest of the crowd. It was a dance about pee. Would they make us pee? How long would it last? Did everyone else remember to go to the toilet before we came in? I shifted my beer uneasily in my hands, not wanting to drink it.

The dancers stood in front of us, staring as we stared. They were wearing diapers. I could not remember a context in which an adult had worn a diaper that was not treated as something sad, or in a comical way. But their expressions were serious.

The sound of the water streams grew louder and more urgent, filling the room. I could not tell when the sounds merged with the sighs and grunts of the performers and became a music on its own. The dancers joined, separated, rejoined. A climax was coming, one that was as unspoken and real as the first piss in the morning.

Finally, the moment came: a performer’s bladder had become full. She went behind a curtain. Her dark silhouette reflected on the white fabric, we saw her silhouetted as she pissed into a latrine, first standing, then squatting. For a moment, her relief was ours. As she finished, she came back out from behind her screen to join us, and a soft scent of urine wafted over the crowd.

This was the first piss of three that evening. The movements of the dancers became slower, but still full of almost invisible tension. They slithered, held each other, lied on the floor and touched each other blindly, like a litter of puppies or babies. The room smelled of pee, yet there was a sense of purity and intimacy.

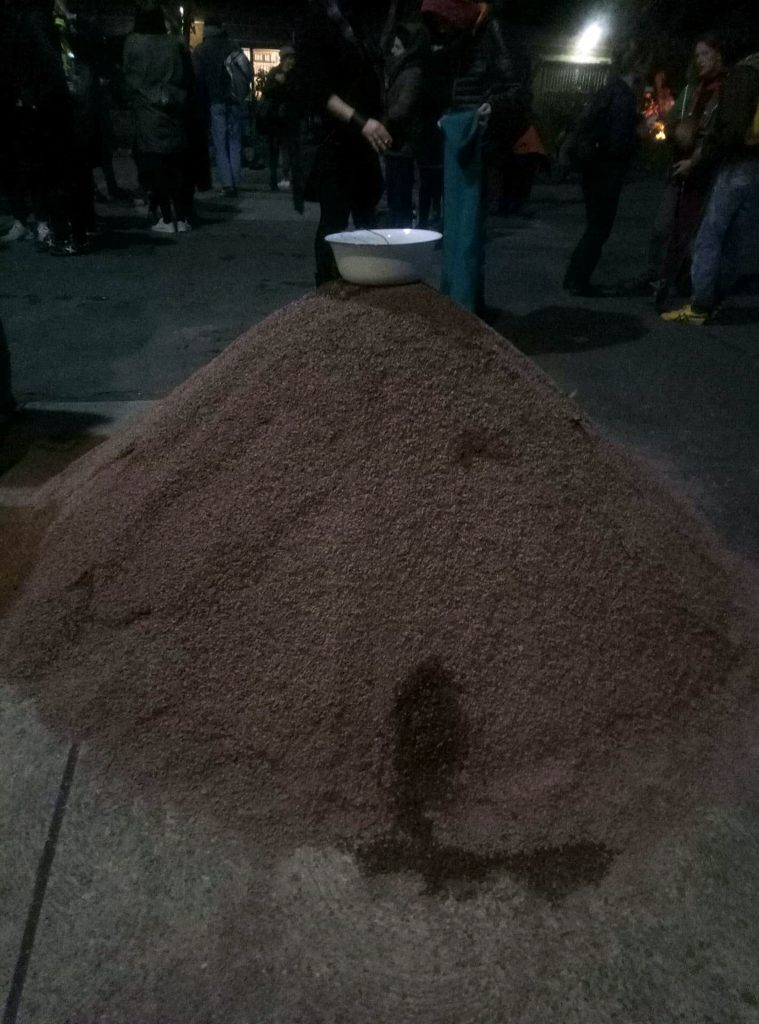

After the pissing, the performers became softer, melting into each other. They ended with a celebration of what they had produced, holding hands and singing around their piss-filled pot. They carried the pot away, singing, like children, an old German saying about hiding your tears. They had also carried us, not through tears, but through an emotion, nameless yet as authentic as joy or despair: the slow buildup of waste in the body. This final moment made me laugh out loud but I know it made other audience members cry – releasing the only sympathetic liquid they could, through their tear ducts.

One of the strongest taboos in Western society is to admit to having a body, something that smells, breathes, excretes, gets hurt, and breaks. It is okay to have one, as long as it is used as a means for other things: we can adorn and embellish it like we could do with a house. We can brag about its strength when we have dominated it through exercise and willpower; when we show it naked, it is with the connotation of sexuality or horror.

We have fetishized our own nakedness into something erotic, we have othered ourselves. But the body as a machine and as a place to live, the body as a living animal, is largely ignored. Part of it could be because acknowledging its material nature is the same as acknowledging death. Accepting ourselves would also mean accepting that a great part of us does not care about us: your lungs do not care why you are pumping air; the heart will keep beating even if it feels broken. And the bladder does not get less full if we try to will it to be empty.

One of the consequences of this corporality taboo is the fact that all bodily fluids are considered dirty and impure, save for tears. Tears can be let out, because they represent an emotion, and therefore serve a noble purpose. However, they are made from the same recycled lymph as vaginal fluids and sweat and urine.

After the performers pissed on stage, my mood towards them changed. I understood that they took us along with them to give us a feeling of a sympathetic bladder. The unashamed nature of the piece asked me why I felt scared and angry with having to think about my bladder and piss. Why be afraid of this truth? There is piss inside me most hours of the day. I accept performers evoking my innate biological reaction to cry, or to become aroused, or to laugh, or even to be very scared, and I tried to accept the evocation of my piss the same way.

I am not a dancer, so I cannot say much about the technique or the structure of the dance. I can only say that afterwards, when I was myself sitting on a white porcelain bowl, alone, I felt a little bit more connected with the rest of the world.

I would have imagined a piss performance playing on the dirty, the sexual, and saying a big ‘fuck you’ to the audience – here’s my piss, it’s gross, fucking deal with it. But this show approached piss with an innocent curiosity. These women were all earthbound squatters, pissing low to the earth and acknowledging this piss as a material outside of them as well as an aspect of their own bodies. And by the end, I saw a glimpse of their peetopia.

Words and photos by Frances Breden and Esther Nelke

Frances Breden is an artist and curator, and has been working with COVEN BERLIN since 2014.

Esther Nelke is a translator, cook, and writer based in Berlin. They are interested in food and community activism. They have collaborated with COVEN BERLIN since 2013.

E A R T H B O U N D S Q U A T T E R S: A PIECE OF PEETOPIAN DANCE, RITUAL OF RELIEF, WASTING TIME WITH OUR WASTES

Initiated by: Carrie McILwain & Johanna Ackva. Created and performed with Joëlle Serret (sound), Josephine Brinkmann, Farina Meyer, Sarah McKee, Pauline Payen, Érica Zíngano (dance)

Performed at: Uferstudios Wedding

1 Comment